Our friend and collaborator from south of the border, Sean Curley, penned this quarterly update for his clients and was kind enough to share it with us. Keeping in mind that the perspective of this piece is for an American audience, the major themes are still very relevant to Canadian investors.

Sean is a Certified Financial Planner, Partner, and Managing Director of Beacon Pointe’s Greenwood Village office in Colorado. He shares our evidence-based investment philosophy and client centric approach to wealth management.

The third quarter added another painful chapter to what had already been an ugly year for markets. While the quarter started on a positive note, August and September saw inflation, interest rates, and the prospect of a recession move again to the forefront of investors’ minds resulting in a 5% loss to the S&P 500 for the quarter, bringing its YTD performance to -24%. International equity markets have also fared poorly, with stocks in developed markets falling more than 9% for the quarter and posting a 27% loss for the year. Emerging market stocks—China being a significant contributor—fared even worse, dropping 12% in Q3, bringing their year-to-date return to -27%. While this has been a difficult year for stock investors, the market’s losses this year are in line with what we have seen during other similar Federal Reserve rate hiking regimes.

Fixed-income investments, on the other hand, are having a historically bad year and have not provided anything close to the stability that investors have come to expect over the last four decades. The U.S. Aggregate Bond Index fell another 5% during the quarter, bringing its YTD performance to a disappointing almost 15%. Municipal bonds have fared a bit better, down about 2% for the quarter and just over 7% for the year. While bonds have helped relative to stocks, they haven’t helped as much as they have during many prior down cycles. With bond prices having fallen dramatically, yields (which move inversely with bond prices) have increased significantly. The yield on the 10-year Treasury closed the third quarter at 3.83%, up from 1.52% at the start of the year.

While we gained some relief from a short-lived mid-June to mid-August summer rally, those gains proved ephemeral as Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell made it abundantly clear in his late-August speech at Jackson Hole that the Fed has every intention of maintaining its hawkish policy until inflation begins to moderate. Or, as one commentator put it, “The beatings will continue until morale improves.” At a minimum, this means expectations are set for another 1.25% in rate hikes over the next two Fed meetings later this year. (By the way, I would try not to get too excited about the potential impact of these expected rate increases on markets or your portfolio since they are likely already baked into security prices, as the market is assuming they are a fait accompli.)

More Things to Worry About…And a Few Bright Spots

Looking forward, markets continue to worry about a spate of bad—or potentially bad—news:

- The prospect of additional rate hikes beyond those already assumed

- An upcoming earnings season that may bring a write-down in expected corporate earnings, some of which may not be yet fully priced into markets

- Concerns that the Fed will overtighten, leading to a full-on recession at some point next year (although there is debate about whether we may already be in a recession)

- Increasing tensions in eastern Europe heightened by Russia’s recent sham referendum and annexation of Ukrainian territory

- Fragility in the UK bond market related to the country’s liability-driven pension scheme, all of which came to light over the last few weeks as markets lost confidence in the wake of the new prime minister’s budgetary missteps and the ensuing economic fallout

Lest you think all of this may have been foreseeable at the start of the year, a late-2021 McKinsey & Co survey of global business leaders showed that Covid-19 was still the then-predominant concern. Relatively few cited inflation. That same survey this year now shows inflation and energy price volatility as the top two concerns, with Covid-19 near the bottom. An even starker example of the perils of prognostication is that Wells Fargo, Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan, and the Royal Bank of Canada all came into the year with 2022 year-end S&P 500 targets north of 5000, while Morgan Stanley, Bank of America/Merrill Lynch, Barclays, and UBS published year-end targets of between 4400 and 4900. By contrast, the S&P 500 closed September under 3600. None of this is meant to be a criticism of any of the aforementioned. It is, however, a reminder that, as Yogi Berra once observed, prediction is hard—especially when it’s about the future.

And yet, not all the news is bad:

- Supply chain issues are unequivocally improving, with shortages easing to levels not seen since October 2020. While it’s hard to say precisely how much of our current inflation woes are supply-chain related, there is no question that supply chain issues have been a meaningful contributor.

- Global freight container costs have fallen more than 60% since September 2021.

- The Manheim Used Vehicle Index, one of the first canaries in the inflation coal mine in 2020, has dropped by 30% since January.

- The price of lumber has fallen back to its June 2020 level.

- The 5- and 10-year TIPS/Treasury break-even inflation rates, which provide a market-based forecast of future inflation, remain anchored at about 2.3% per year over the next five and ten years.

These are all positive indicators for the forward-looking trajectory of inflation and provide some hope that a decrease in inflation will eventually provide the Fed some breathing room.

And not to be too perversely pollyannaish, but in other good news for forward-looking stock owners, market bears outnumbered market bulls by over 40%, according to a late-September poll conducted by the American Association of Individual Investors (AAII). More than 60% of investors were bearish, and only 20% were bullish. This is among the most negative readings ever recorded and joined just four other years out of the last 35 when more than 60% of AAII respondents expressed hopelessness.

Wait! What? How can this possibly be good news?

Because in the four other instances when this has occurred since the survey’s 1987 inception, the S&P 500 returns over the next year were +22%, +32%, +7%, and +57%.

Similarly, the table below from Ben Carlson, writing at A Wealth of Common Sense, also offers reason to be encouraged despite what has been a year of much despair.

S&P 500 Returns Following Prior 25% Downturns Since 1950

*** Note that the subsequent returns are dated not from when the market bottomed, but from the first of the next month after the S&P 500 initially crossed the -25% mark, as the market has just recently done.

Yes, this looks a lot like the table from last quarter’s commentary that showed how markets have fared after a significant downturn, but this one is even better(!) as, historically speaking, prospective returns look even better after a 25% dip than after a 15% dip as was shown in last quarter’s version. There is a lot of green on that table! In all but one of the ensuing one-, three-, five, and ten-year periods that followed a 25% dip, the S&P 500 was positive —and in many cases, robustly so. Of course, none of this tells us what the future will be with any certainty, but it does provide reason for encouragement regardless of what the near term may hold.

And, not to go overboard on charts, but here’s one more from Callie Cox at eToro. This one makes a related point—namely, the bull market gains that follow a bear market have historically dwarfed the dips. This is why markets have increased over time and why owning stocks has been so accretive to the wealth of the patient and disciplined investor.

Bear Markets and the Recoveries That Followed

But What If We Have a Recession?

JP Morgan’s CEO, Jamie Dimon, made news this past week with his speculation that the U.S. is likely to tip into a recession in the next six to nine months. This caused markets to tumble a bit on the day the story broke. Such is the news-market cycle we’re living in.

Yes, the odds of a recession, at least as the punditry has been tracking them, have grown as the year has progressed. Some put the odds at 65%; others as high as 98%. And, there are some who make the case that we’re already in a recession, although that’s a bit hard to fathom given the current job numbers, which continue to be strong. Unlike much of the world, where the definition of a recession is two successive quarters of contracting GDP, the U.S. definition is a bit squishier and is based on myriad factors, some of which aren’t known until well after the fact. Consequently, recessions are sometimes not declared as such until six or even twelve months after their actual start.

Furthermore, markets, which tend to be forward-looking, have often declined well in advance of recession, just as we’ve seen this year. Should we tip into recession as Mr. Dimon predicts, this will likely be the most predicted recession of all time, and it’s fair to assume that some component of the market’s drop this year is accounting for that possibility. However, it’s hard to know just how much of a recession is priced in or how much corporate earnings may drop. No two recessions are alike, and this one (if we’re actually heading into one) is a case in point, with the jobs picture continuing to look surprisingly rosy despite what the press would make out to be the end of the economic world as we know it.

Here’s a look from mutual fund company Avantis at how the U.S. market (as measured by the CRSP U.S. Total Market Index) fared, on average, during prior recessions over the last 50 years.

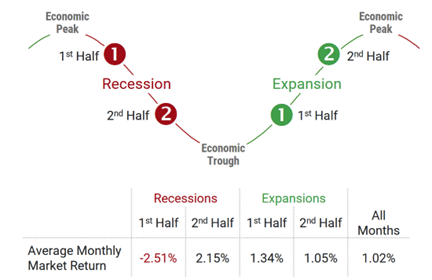

Note that the average monthly stock market return DURING a recession is -0.21% per month. This being the average, it implies that during some recessions, markets have done worse than -0.21% per month on average, and in others, better than -0.21% per month. However, breaking this down further to look at market returns during the first half of the average recession vs. the second half of the average recession (see graphic below), we can see that the U.S. market typically (and unsurprisingly) fell 2.51% per month during the first half, but gained 2.15% per month during the second half!

Obviously, the ideal thing to do would be to get out of the way before a recession arrives (although markets typically fall well in advance of a recession) and then get back in at about the trough. Of course, this is easier to do with the benefit of hindsight, especially given that the National Bureau of Economic Recessions, the official arbiter of recessions in the U.S, often doesn’t date the beginning and end of a recession until well after they have started or ended.

With that as a prelude, you might wonder, is there anything that can be done to protect a portfolio?

The answer is that, yes, we could move out of equities and to the sidelines trying to staunch further portfolio declines. And, making that even more tempting is that cash is now providing a yield much more attractive than just a year ago. However, as attractive as this appears at first blush, in practice, it’s typically much less attractive—if even achievable—for two reasons. First, this seldom works out well in the real world, especially getting out this far into a downturn (see Carlson’s earlier chart). When people do move to the sidelines, they are almost always doing so because they have been painfully primed to do so by a recent bad run in markets, as we’ve just been through. Secondly, while getting out is the easier part of the equation (and to be fair, it’s not uncommon to see clients miss at least some downside after doing so), it’s rare to see anyone put the other important part of the equation (i.e., the getting back in part) together with the first part and make the two, in their totality, a winning exercise. This is typically because when the market turns—often well in advance of convincing economic data, it turns viciously and is often quickly above the point where they got out, while they watch with incredulity, not knowing what to do.

Perhaps even more importantly is that, uncomfortable though this may be, none of what we are experiencing this year is unexpected or unanticipated in the context of a long-term retirement plan. We don’t assume that it will always be smooth sailing, nor do we base any client’s projection on the assumption that markets will always behave themselves or that returns are predictable in the short term. Generally speaking, volatile markets in and of themselves should not be a primary impetus to change a well-thought-out investment plan. However, if your objectives have changed (or you have belatedly realized that the ride you’re getting is not the one you thought you signed up for), then we should chat.

And, Lastly…

With all of that said, we realize what a challenging year this has been for investors. The daily barrage of mostly negative economic news, often delivered breathlessly, and heightened market volatility have only added to the sense of uncertainty. And yet, despite all of that, it may be helpful to keep several things in mind:

- Every bear market is different but always brings with it a vague sense that the economic world as we know it might end. It may feel that way but, historically, it hasn’t yet and most likely won’t.

- While the very normal human tendency is to want to make portfolio adjustments, even if only to regain a sense of control, doing so this far into a downturn almost always results in a decrease to future expected returns, even if it may bring some short-term comfort.

- Historically, downturns like this one have been a time when market wealth gets transferred from the hands of impatient, undisciplined, and unsteady investors and into the pockets of the patient, disciplined, and steadfast. Much better — albeit more difficult —to be the latter than the former!

- The focus of any reasonably long-term, retirement-oriented investment plan shouldn’t be just the next year or two but instead the next decade or two.

- Said another way, the most significant risk most retirees (or eventual retirees) will face is not market volatility but the slow erosion of their purchasing power over what, for many, is a decade(s)-long retirement. Conflating what feels like risk in the short-term (volatility) for what most assuredly is the ultimate long-term risk (diminished purchasing power) too often leads to the mother of all investing mistakes —turning a temporary fluctuation in market value into a permanent loss of capital.

So, despite the economic storm clouds that have gathered, it would be worth remembering that much about today’s market environment is more favorable for investors than it was at the end of last year, even if it doesn’t feel that way. Bond yields are higher, and stock market valuations are lower, both of which portend higher expected returns for investors. Yes, it feels so much worse than that because of the terrible year we’ve had so far, but investing decisions —like most decisions in life —are better made by looking through the windshield than in the rearview mirror. And, lastly, during difficult stretches like these, remember that prior downturns have eventually been followed by even larger recoveries that have been accretive to the wealth of patient and disciplined investors. The present discomfort notwithstanding, there is no reason to believe this time will be any different.